1,000 GW of wind power: the 4 big mistakes and the big opportunity

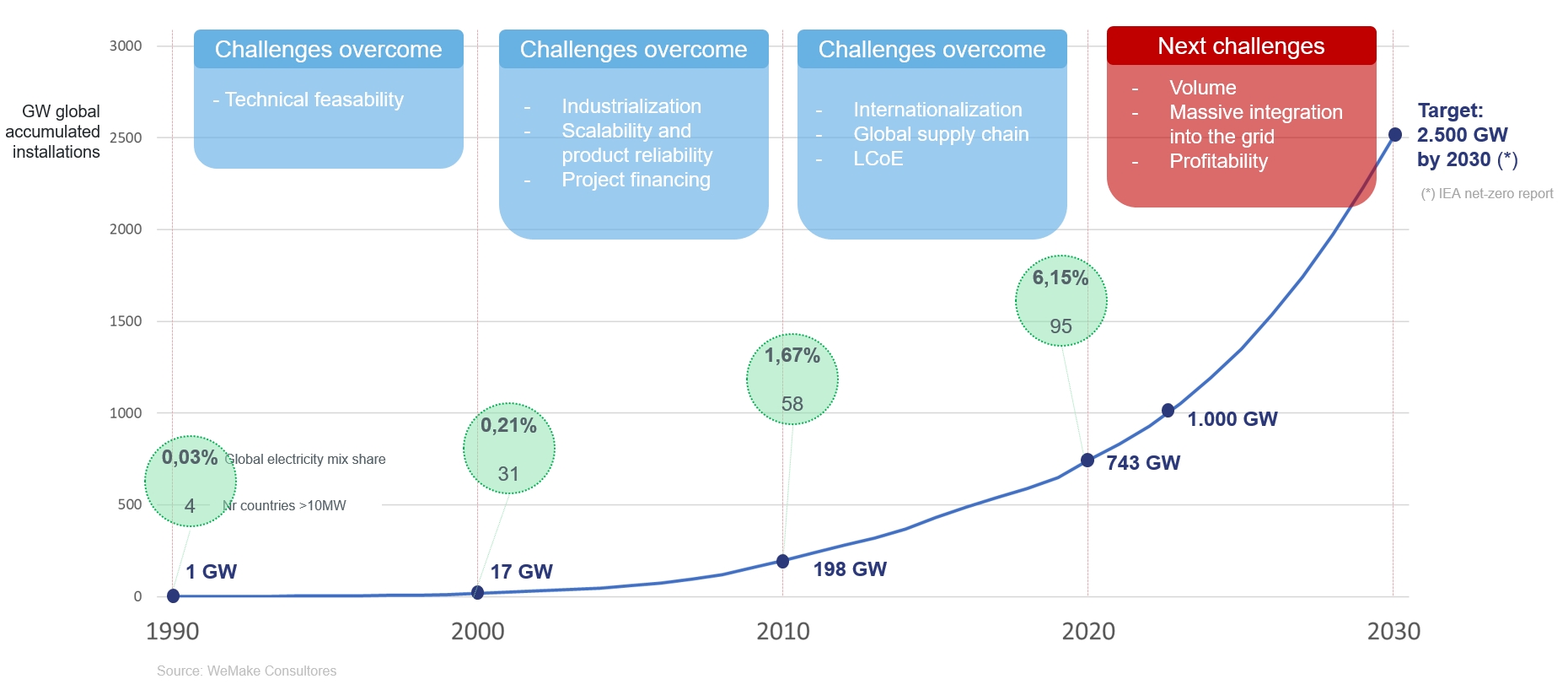

Already 1,000 GW of wind power is installed worldwide. This is an impressive figure considering that large-scale wind technology started some 40 years ago, but it is even more impressive that, according to all forecasts, we will see the second TW installed in less than 10 years from now. Taking advantage of the milestone, it is a good time to look back and briefly review some key moments in the sector.

1990-2000

While in the previous decade pioneers such as Ecotecnia or MADE in Spain, Vestas in Denmark or Enercon in Germany developed the first large-scale wind turbine concepts, it was in the 1990s that the technological concepts matured and demonstrated their reliability and scalability.

This was the golden decade of turbines of less than 1 MW and rotors of less than 50m, with the V42/V47 from Vestas at the forefront and now legendary models such as the Enercon E-40 or the Neg Micon 44-48. In Spain, Gamesa with its legendary G47 (under licence from Vestas). MADE with its AE-46 or Ecotecnia with its ECO44 began to manufacture and install in series a technology that until then had been very marginal.

We still see many wind farms from that era with very reliable turbines and very well maintained by their owners, such as the El Perdón wind farm near Pamplona, built by Gamesa for Acciona with G4X turbines, which is still in operation 30 years later.

2000-2010

From a product point of view, this decade is undoubtedly the decade of the 1.5MW and 2 MW turbines. It was in these years that the platforms that are still the most numerous globally were installed en masse: GE1.5 MW, Vestas 2 MW, Gamesa G8X 2.0 MW, Enercon E-70, etc. These are models that inherited the technology of the <1 MW models but raised the level of industrialisation and reliability. And a large part of the success of these models was their long life, which allowed field experience to be applied to the new units, making the technology more robust every year.

Another key tool for the take-off of wind power globally was project finance. It was obviously not a concept invented for this sector, but the fact that it was widely used to finance wind projects was very important in making many projects viable.

For the Spanish sector, it was a golden decade. Companies such as Gamesa, Acciona and Iberdrola took advantage of local growth to gain muscle and make the leap to international markets.

2010-2020

This decade was the decade of the explosion of the wind energy market, but it was also the decade in which the seeds were sown for the major structural problems that the sector is suffering today.

The wind business had traditionally been a subsidised sector, with feed-in-tariffs in some cases too generous. This had the positive consequence of accelerating growth and attracting investment but, on the contrary, it had created the perception of being an expensive and inefficient technology. In order to remove this label, the sector began to use the concept of LCoE (levelised Cost of Energy), a metric with which to demonstrate its cost improvements to the world.

Against this backdrop came the great financial crisis of 2008. States had to cut costs and subsidies for renewables were eliminated in many countries. In Spain they were eliminated retroactively through RD1/2012. In many countries, including Spain, the sector came to a complete standstill due to the lack of aid.

But far from killing the sector, this has a key consequence: it accelerates the transition from feed-in tariffs to competitive auctions. And this is where hunger meets hunger: a sector eager to prove that it is not expensive by wielding the sword of the LCoE, together with states eager to obtain the cheapest possible electricity through auctions. Moreover, in these auctions, it is very common to bring together all renewables, including a technology that at the time was immature and quite marginal, but which would prove in the future to be the worst company to go to auction with… solar.

And this is the sector’s first big mistake that marks the beginning of its “race to hell”. It is very easy to make these analyses in retrospect, but the truth is that in those years, all of us who worked in the sector were proud of the record prices that were set at auction after auction: Morocco 2016, Round 2 offshore in the UK, Saudi Arabia in 2019, Portugal, Spain in 2020. In addition, wind power was trying to fight on a level playing field with solar power in terms of price, something that we now see as suicidal but which seemed viable in those years.

And how was it possible for the entire industry to join this “race to the bottom”? Remember that the OEMs had started the decade with great success based on very reliable platforms that they manufactured and installed in large volumes. But come the auctions and the great competition between developers to take the capacity, a downward price war starts and the OEMs make their second big mistake by agreeing to enter this war. In a nutshell, this is how it happened:

- The developer wins the auction with a very aggressive price and therefore needs a LCoE upgrade from the OEM.

- The OEM knows that it can achieve this reduction only if it launches a new, more powerful turbine and as the project is several years away (especially offshore) and competition is fierce, it accepts the developer’s challenge.

- This leads to a frantic race for ever larger new models, the third big mistake in the sector.

But this race soon proves unsustainable: the rapid launch of new models eliminates two of the pillars of OEM success: reliability, as there is no material time to make platforms reliable, and volume, as far fewer units of each model are produced.

Although at the end of the decade there are already industry voices warning that this rate of launches is unsustainable for OEMs, low commodity prices are helping the downward price race to continue, but then comes the perfect storm…

2020-2023

And then came the pandemic, Ukraine’s war and the subsequent brutal rise in the cost of raw materials and logistics.

What should have been an industry-wide proportionate hit was particularly hard on the OEMs, and why was this the case? Wasn’t it the developers who were committing to low prices? And it is here that the fourth big mistake of the OEMs is revealed: the tremendous imbalance of risk that existed in the business.

Basically, the OEMs were making the investments to develop new products, paying for the reliability problems of the first few years and with the risk that costs would rise on contracts already signed, as they did.

The long lead times from contract signature to execution (especially in offshore) mean that the risk of things happening in those periods is very high, and OEMs did not (or could not) share that risk with their clients.

Moreover, as is now being demonstrated, the level of warranty provisions for new models was unrealistic and left OEMs with the full risk of launching unreliable machines, with the added bonus of having extended warranty periods with very long full service contracts.

What next?

It is now becoming clear that solving the four big mistakes is neither easy nor quick. All OEMs are working on it (some with more success than others) but the messages from the CEOs of Vestas, SiemensGamesa, GE and Nordex are very clear:

- Raising prices and avoiding price wars

- Slowdown in the pace of new product launches. Simplification of the product catalogue

- Signing of more balanced risk-sharing contracts

- Encouraging “value” rather than “price” auctions

The great opportunity

Many wonder how the owners/shareholders of the large OEMs can continue to bear the massive losses and why they have not already thrown in the towel. The answer is simple: because despite the current problems, wind is going to be an indispensable piece in the energy transition puzzle. To endure is to succeed, and those that remain after this harsh winter of losses and problems will have more demand than they can supply, as well as a technology that the more solar is installed, the more valuable it will be due to its production profile and its differential characteristics. Just as in the great financial crisis of 2008 there were banks that were too big to fail, OEMs are too much needed to fail.

energy-charts.info

energy-charts.info